|

AUTOZINE TECHNICAL SCHOOL

Manual Transmission Overview

Manual transmission might be almost dead in the USA – only 4 percent of all new cars sold there are equipped with stick-shift – but in the rest of the world it is still the choice of the majority. For example, 75 percent of UK motorists bought manual transmission in 2013, and this figure does not include derivatives like automated manual and dual-clutch transmission. Most other European countries have similar findings. Manual gearboxes are cheap, fuel-efficient and fun to drive, so they are not going to extinct any time soon. Frankly, manual transmission technology progressed little in the past 30 years or so. While automatic transmission evolved from 4 to 8 or more ratios, manual inched from 5 to 6 gears. Slower cars still employ 5, while only Porsche, Corvette and Aston opt for 7, yet the top gear is actually an overdrive to save fuel. Any more gears would have put too much work to the driver and seen as tiresome. Therefore, manual is unlikely to get more ratios in the future, thus it will lose ground to automatic in both acceleration and fuel economy. Disappointingly, manual transmission makers did not make good use of the past 30 years to improve gearshift quality. There are still too many examples being criticized for balky or rubbery linkage, or poorly weighted clutches. Ridiculously, many motoring journalists revisited the classic cars of the 1960s or 70s and praised they had better gearshifts than many modern cars. Instead of making the basics better, development of manual transmissions has been concentrated on mechatronics to make them semi-automatic. You can't argue with that, because the increasingly congested traffic is turning more motorists to the automatic camp. Fortunately, with the introduction of dual-clutch transmission, the manual camp gets a big boost, especially in sports and supercar segments. Clutchless manual - e.g. Saab Sensonic Clutchless manual transmission is simply a manual gearbox mated to an electronic-controlled clutch. It can therefore skip the clutch pedal. The driver just needs to work on the shifter. There are sensors added to monitor the pressure of shifter and accelerator pedal. In case the shifter is pushed and the accelerator is relieved, the ECU will signal the clutch to disengage, and continue monitoring the progress of gearchange until it has finished, then engage the clutch again. I believe the earliest electronic-controlled clutchless manuals were developed by Valeo for Ferrari Mondial T (1991), and Fichtel and Sachs for RUF 911 BTR (1992). They did not catch the attention of volume makers until Saab introduced its version called "Sensonic" in 1993. Road test found Saab 900 Sensonic ran as fast as the manual version. Nevertheless, it did not sell well thus went out of production in 1998. Since its demise, no one followed its footstep.  Clutchless manual cost just a fraction more than a conventional manual. It relieved driving effort, especially in traffic jam, making gearshift easier while having no disadvantages of automatic transmission. It was a logical step to improve conventional manual transmission, albeit a small step. Automatic rev matching In 2008, Nissan 370Z introduced a new kind of manual transmission technology that makes downshift smoother and faster: automatic rev matching. It is so useful that nowadays becomes a standard feature on many manual transmission cars. Rev-matching technique is not new, but it used to be done by human. Advanced drivers use heel-and-toe action to brake the car while applying throttle, raising the engine rev to match the lower gear to be engaged. During a downshift, the gearbox input shaft will be speeded up instantly due to the higher ratio. If the engine is not speeded up as well, when the clutch closes, the speed difference between engine and gearbox will cause a jolt. The faster-spinnig gearbox input shaft will push the engine crankshaft to turn faster. This process takes time, during which the clutch is slipping. If the driver can blip the throttle appropriately before the clutch is engaged, the engine will be speeded up to match the speed of the gearbox. Consequently, the downshift can be completed smoothly and quickly. Automatic rev matching is the same, just implement it with electronics. Sensors placed at the clutch pedal and gearstick sense the intention of the driver. If the clutch pedal is pressed and the gearstick senses a pressure towards a lower gear, the ECU will tell the engine to blip throttle, raising the rev to match the speed of next gear. Since drive-by-wire throttle is already widely available, and the additional sensors already existed since the days of Saab Sensonic, automatic rev matching is cheap and easy to implement. No wonder it can be widespread in just a few years. What about upshift? It is not much a concern. When you upshift, the gearbox input shaft will slow down instantly. At the same time, the engine is also slowed down as you release the throttle during the clutch engagement. Therefore the speed difference is small, causing little jolt and losing little time. No-lift shift If Automatic rev matching can alter the throttle during gearshift, why not simply ditch the need of backing off throttle? That's the logic behind General Motor's "No-lift shift" feature (by the way, a very American name). No-lift shift was first introduced on the 2008 Chevrolet HHR SS and Cobalt SS turbo, and then extended to many high-performance cars of the group. It is enabled only in full-throttle acceleration, mainly for standing-start launch. The driver can keep planting his foot on the throttle during gearshift, just need to cencentrate on the clutch and shifter. The ECU scales back the throttle automatically during shift, but not completely back off as it needs to keep the turbo on boost. Put it simply, No-lift shift is actually part of the functions offered by a typical launch control. A launch control controls also the clutch and gearshift if mated with automatic, automated manual or DCT gearbox. No-lift shift takes care of the throttle only, which is as far as a manual transmission car can do. Ferrari F1 Automated manual, as indicted by its name, is a manual transmission added with automatic function. It is not to be confused with something like Porsche Tiptronic, which is automatic transmission added with manual function. One of the first production automated manuals was Ferrari's F1 system, debuted on F355 F1 in 1997. As indicated by its name, the transmission of F355 F1 was developed from Ferrari's Formula One semi-automatic gearbox which debuted in 1989, powering Nigel Mansell's 640 racer to win the opening race at Brazil from Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna (I can still remember how stunning when I watched it live on TV). Although the Ferrari did not win the championship that year, it demonstrated the superiority of semi-automatic and eventually became standard for every F1 team. The system used in F355 F1 was based on the 6-speed manual gearbox of the standard F355, but with the mechanical gearshift mechanism replaced with an electronic clutch and a high-pressure hydraulic shift actuator. It offered 3 operating modes. In normal city driving, most drivers may choose the fully automatic mode, in which the computer made gearshift automatically by analysing engine rev, load and throttle. However, it was not as smooth as a real automatic gearbox because of the lack of hydraulic torque converter.

For higher performance, pushed the switch on transmission tunnel to Sport position and the gearbox would be under the driver's control. Gearshift was carried out by flicking the large paddles mounted at the steering column and behind the steering wheel. One paddle for upshift and another for downshift. The box integrated clutch action and gearshift remarkably well. Within milliseconds from the moment the driver pressed the shift paddle, the computer started simulating how a professional racing driver worked - eased the electronic throttle, disengaged the electronic clutch, and then signalled the hydraulic actuator to shift to another gear - all these actions were taken progressively and smoothly. During hard acceleration, upshift would be made at over 8,000 rpm and the whole process took as little as 150ms. This is why the F355 F1 showed virtually no loss of performance compared with the standard 6-speed manual. In reality, it might be even quicker than the manual because the driver no longer needed to take care of clutch and throttle, or wasted time to travel his hand from steering wheel to gear lever mounted on central tunnel. He could concentrate on only steering and gearshift. The last operating mode was a medium semi-automatic mode. In this mode, gearchange took place at only 6,000 rpm. This provided a less urgent acceleration but smoother shift quality. It might not be faster than the fully automatic mode, but it got the driver involved so to give more driving pleasure. The F1 system was developed in conjunction by Ferrari and Magneti-Marelli. It weighed and cost half way between manual and automatic transmission, but provided the advantages of both. No wonder some 90% of the F355 sold were equipped with the F1 box. In the following 360 Modena, Ferrari improved its software to include throttle blipping on downshift (yes, automatic rev matching appeared well before Nissan 370Z, albeit on automated manual), guaranteeing a faster and smoother transition. Most other Ferraris also turned to the F1 box until the late 2000s, when California and 458 Italia introduced twin-clutch gearboxes. It was the most acclaimed automated manual gearbox ever built. Alfa Romeo Selespeed Ferrari's automated manual gearbox was called "Selespeed" internally, but Maranello opted to sell it under the name "F1" for marketing reasons. Interestingly, when its technology was transferred to sister company Alfa Romeo, so was the name Selespeed. The first Alfa model using this gearbox was 156 Selespeed, debuted in 1999. It was also the first application of automated manual on mainstream production cars.

Like the unit of F355 F1, the Selespeed was derived from the regular 5-speed manual serving other 156 models but added with an electrohydraulic gearchange actuator and an electronic-conrolled clutch. Its operation was mostly the same as Ferrari's, but the gearshift was controlled by two buttons located at the steering wheel instead of column-mounted paddles (later version on Alfa 147 turned to paddles). Its gearshift was not as fast as Ferrari's, of course, normally taking 1 to 1.5 seconds. Even in Sport mode it still took some 700ms, so keen drivers had better to opt for the regular manual gearbox. BMW SMG  Introduced

to the market in early 1997, BMW's SMG (Sequential Manual

Gearbox) was the world's first production automated manual gearbox,

beating Ferrari F1 by a few months. It was offered on the E36 M3 Evo

exclusively as an optional equipment. Introduced

to the market in early 1997, BMW's SMG (Sequential Manual

Gearbox) was the world's first production automated manual gearbox,

beating Ferrari F1 by a few months. It was offered on the E36 M3 Evo

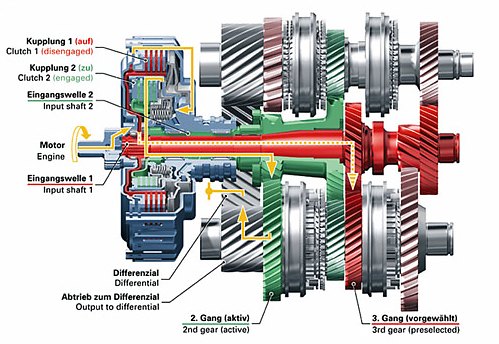

exclusively as an optional equipment.The SMG was developed jointly by BMW, Getrag and Sachs. Based on the Getrag 6-speed manual box serving the standard M3, it added high-pressure hydraulic actuator to carry out gearchange and mated with an automatic clutch, both were controlled by ECU. While Ferrari used paddles to trigger gearchange, the SMG employed a conventional shift lever at the transmission tunnel. However, it worked like the sequential transmissions on touring cars, i.e. by push-pull action, so it was faster and easier to control. A switch located near the shifter panel was used to change between manual and automatic modes. Compared with Ferrari F1 box, the first generation SMG was not quite as fast, taking a minimum 220ms. As a result, contemporary road tests found it sacrificed a bit performance compared with the standard manual gearbox. Nevertheless, BMW claimed in the real world like Nurburgring the M3 SMG could outrun the manual car, since the driver could concentrate more on steering, throttle and braking. The first generation SMG had many rough edges, including jerky shift quality and reliability issues. However, the idea of combining automatic and race-car-style sequential gearshift was proved to be popular. Since its introduction, about 50% of the E36 M3 sold were fitted with SMG. In the following E46 M3, the SMG was developed into SMG II. It offered quicker shift and 11 modes - 5 automatic and 6 manual modes with different speed and smoothness. At the hottest S6 mode, gearshift took as little as 80ms, though at the price of smoothness. The contemporary M5 and M6 also employed a version of the SMG II. As the SMG, or just any single-clutch automated manual in general, never quite manage to offer seamless gearshifts, BMW eventually abandoned it for the new twin-clutch gearbox from 2008. Today, automated manual is a technology well passed its peak. Only 2 types of cars remain using it: small cars that could not afford automatic an transmission, or very high power supercars that failed to find a suitable DCT (such as Koenigsegg, Pagani or Lamborghini). Twin-clutch gearbox, or dual-clutch transmission (DCT), is undoubtedly a revolutionary technology for manual transmission. Its impact to the automotive world is even bigger than automated manual gearbox described above. The world's first production twin-clutch gearbox was developed jointly by Volkswagen group and transmission maker BorgWarner, which called it "DualTronic". It was launched on Audi TT 3.2 in 2003 under the name DSG (Direct-Shift Gearbox). Like automated manual gearbox, DSG can operate as a semi-automatic, where the driver changes gears via buttons, paddles or conventional shifter. There is no clutch pedal, because the clutch is automatic while the gearshift is implemented by electro-hydraulic actuators. For relaxed driving, there is also a full automatic mode, where computer determines which gear to be selected. So, what’s the difference between it and other automated manual gearbox?  Unlike conventional

gearboxes, DSG uses 2 clutches - one clutch connects to the odd gears

(1st, 3rd and 5th) while another clutch connects to even gears (2nd,

4th and 6th). This enable it to shift far smoother and faster than

conventional gearboxes. Unlike conventional

gearboxes, DSG uses 2 clutches - one clutch connects to the odd gears

(1st, 3rd and 5th) while another clutch connects to even gears (2nd,

4th and 6th). This enable it to shift far smoother and faster than

conventional gearboxes.Why? Let us see how a conventional gearbox work first: when a driver wants to change from one gear to another, he presses down the clutch pedal, thus the engine is disconnected from the gearbox. During this period, no power is transmitted to the gearbox, thus the driver can shift gears. When it is done, he engages the clutch again, then power is transmitted again to the gearbox. As you can see, the power delivery changes from ON to OFF to ON during gearshift. How smooth the change depends on how skillful the driver cooperate the clutch and throttle. Automated gearbox like Ferrari F1 is similar. The only difference is that the clutch and gearshift are operated by computer via hydraulic actuators. The ON-OFF-ON power delivery still exists. In contrast, an automatic transmission with torque converter does not has this problem. Twin-clutch gearbox can overcome the ON-OFF-ON problem too, thanks to the twin-clutch design which enables it to "pre-select" the next gear. Take this example: assuming the car is accelerating at 2nd gear. The clutch controlling the even gears is now engaged while another clutch is disengaged. From the data taken at throttle position and rev counter, the computer knows that the driver will select 3rd soon, thus it will connect the 3rd gear. Because at this moment the clutch for odd gears is disengaged, the pre-selection of 3rd will not affect the 2nd gear currently running. When the driver touches the gear-shift paddle, computer signals the even-gear clutch to disengage and simultaneously the odd-gear clutch to engage. In this way, gear is changed from 2nd to 3rd instantaneously, without any OFF period, without any delay - the only delay is caused by the smooth disengagement and engagement of the two clutches. Therefore power delivery is smooth and uninterrupted. Pre-selection of gears quickens the shift a lot. Upshift takes just 8ms, 10 times quicker than BMW SMG II. Downshift is less impressive, because the gearbox need to wait for the throttle blipping to match gearbox speed with engine speed. Change down a gear therefore takes 600ms. Changing down a few gears could be more complicated. The most complicated is from 6th to 2nd (both are controlled by the same clutch while the distance between the two gears is the longest). It needs to change to 5th (controlled by another clutch) temporarily before 2nd is selected. This takes 900ms. To package 2 clutches in limited space, the BorgWarner design cleverly runs an input shaft inside another hollow input shaft. Besides, more space is saved by using multi-plate clutches which are far smaller in diameter than conventional clutches. Multi-plate clutches also allow finer control of engagement speed versus smoothness. Depending on driving style, computer can easily change the gearshift speed/smoothness settings. Since 2003, Volkswagen group has been using twin-clutch gearboxes on millions of its cars, including those Audis dubbed S tronic. They serve from the small Polo to as high as Lamborghini Huracan or even Bugatti Veyron. High-end sports cars like Ferrari, Porsche and McLaren have all turned to this technology thanks to the work of Getrag, ZF and Graziano, while mainstream manufacturers like FCA, Renault, Mercedes, Hyundai and Honda also put them to mainstream cars. In 2019, Koenigsegg introduced a new type of manual transmission called Light Speed Transmission (LST) on its Jesko supercar. It has 9 forward ratios, 7 clutches but no sync rings. Koenigsegg claims it shifts as quick as DCT but is much lighter for its class (90kg instead of 140kg) and more compact. Brilliantly, the LST is designed and patented by Koenigsegg itself.  From the drawing below, you can see the

internal structure of the LST. Like a DCT, it has 3 shafts, i.e. an

input shaft, an output shaft and an intermediate shaft. 7 multiplate

clutches are spreaded between the last two, responsible for engaging

and disengaging individual gears. Worth noting is, there is no

conventional clutch and flywheel before the input shaft, as the latter

is connected straight to the engine. The gears on the input shaft and

the gears coupling from them are always turning by the engine, so their

inertia does the job of a conventional flywheel. This saves weight.

When the car is idling, the input shaft is spinning, driving 3 of the gears on the intermediate shaft as well as the frontmost gear on the output shaft. Since all clutches are disengaged, no power is transmitted to the output shaft.  When 1st gear is selected, the first

clutch of the intermediate shaft and the second clutch of the output

shaft engage their respective gears. Power is therefore transmitted to

the output shaft through the 2 pairs of coupling gears. As you can see

from the sizes of the gears, the speed of rotation is stepped down in

each coupling while torque is stepped up.

When 2nd gear is selected, power still goes through the first coupling gears, but this time the output shaft engages another gear, whose gear ratio speeds up the rotation a little.  Similarly, at 3rd, the last and smallest

gear of the output shaft is engaged, resulting in faster rotation still.

At 4th gear, it engages another, larger

gear on the input shaft, which speeds up the rotation further.

Now I think you can work out the rest...

In short, the LST has a 2-stage multiplication, each stage has 3 gear ratios to choose from, so in total you have 9 forward ratios. It is pretty clever. If it were a conventional manual gearbox or dual-clutch gearbox, it would have needed 9 pairs or 18 gears to achieve 9-speed. Now it needs only 12 gears, resulting in significant saving of weight and space.  For reverse, the frontmost gear of the output shaft is coupled directly from the input shaft, resulting in reverse rotation. Another advantage of the LST is, it can shift across multiple gears, say, from 6th to 2nd. In contrast, a DCT needs to change to 5th first and then 2nd, because even gears share the same clutch. The LST has one clutch serving each gear, so it has no such problems. Now you might wonder if other car makers are going to buy into this idea. Well, the LST is undeniably clever, but it works best for supercars. Most cars on the market are fine with 6 or 7 speeds, so they need only 12 or 14 gears. If LST is redesigned to offer 6 speeds only, it will require 10 gears, saving only 2 gears. For 7-speed, it needs 12 gears like the current design, again saving 2 gears from its rivals. Then you have to consider the additional weight and costs contributed by all those clutches and their hydraulic system. Whether the end product will still be lighter than a 6 or 7-speed DCT, I don't know, but I am quite sure that it will be more expensive to build. However, for a supercar with a top speed potentially good for 300mph and a price tag with more zeros than you can count, Koenigsegg is best suited to this kind of transmission. |

||||||

| Copyright© 1997-2019 by Mark Wan @ AutoZine |