The supercar booming period

running from the late 1980s to mid-1990s created a lot of dream

cars as well as many unfulfilled dreams. Born just before the burst of

the supercar

bubble, McLaren F1 was the best of them all. Not only by far the

fastest, it was also the best engineered and the most innovative one.

Thanks must go to its creator, Gordon Murray.

Murray is no stranger to motorsport fans. Before moving to road car design, he was already a famed Formula One car designer. He had a C.V. everybody would envy – the Brabham BT46B ground effect "fan car", the low-slung Brabham BT55 and the most dominant F1 car in history, McLaren MP4/4, which won 15 out of 16 races with Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost. Innovation seems to be the middle name of Gordon Murray. In 1989, attracted by the boom of supercar market, McLaren boss Ron Dennis decided to expand its business to road car production. As a result, McLaren Cars was founded and Murray was assigned as chief engineer of the supercar, which was soon named as "F1" for obvious reasons.  Without bounded by conventional thinking, Murray pioneered

the idea of 3-seat layout, which has the driver sitting centrally and

sandwiched by two passengers situated slightly behind. This has many

advantages: it gives the driver the most accurate view on both sides;

it allows the driver seat to be positioned further forward for better

visibility, and subsequently the fuel tank also moved forward for

better balance; it avoided offset pedals as the foot well is no longer

blocked by wheel well; and finally, it accommodates Mr. Murray, his

wife and mother-in-law simultaneously. The only downside is the

difficulty to access the driver seat, though partially relieved by

using butterfly doors. Nevertheless, it is a price worth

paying.

Another innovation is its full carbon-fiber construction, i.e. not only body panels but also chassis. Since the days of Ferrari 288GTO, supercars had been using exotic materials like carbon-fiber and Kevlar to keep weight down. However, they still employed traditional tubular steel chassis underneath the advanced bodyworks. Being the pioneer of carbon-fiber chassis in Formula One, McLaren once again rewrote the history book with the first carbon-fiber monocoque chassis for road cars. Yes, it was very expensive to build, but it showed the car's relentless pursuit of lightness.  In fact, its lightweight philosophy went much deeper than

the carbon chassis. For example, its suspension wishbones were made of

solid blocks of aluminum alloy CNC-machined to

shape so to offer the required strength at the minimum

weight, just in Formula One practice. Its Brembo brakes had lightweight

monobloc aluminum calipers, something unheard until then. Its 17-inch

wheels were made of magnesium, a metal even lighter than

aluminum. Moreover, Murray decided that a purist car should go without

any artificial driver aids, no matter ABS, traction control or

stability

control. For the benefit of weight, not even power steering and brake

servo were offered.

Trivial things were also paid attention. For example, the engine compartment used pure gold foils to insulate from heat, saving the need of insulating foams. The tool kit was made of titanium. The driver seat was the thinnest carbon-fiber item I have ever seen. It was non-adjustable, of course, but McLaren would tailor the seat and pedal positions to each customer. However, don't think the F1 was a thinnly disguised race car. Far from it actually, Gordon Murray insisted it to be a practical road car, so it did not sacrifice air-con, power windows, central locking and stereo. The latter was specially developed by Kenwood, and was the world's lightest audio system with 10-CD changer. No wonder the F1 weighs only 1138 kg. For comparison, Bugatti EB110 weighed a good 430 kg more than it, and today's Veyron is 810 kg heavier ! This mean, despite of its disadvantage in power, the old McLaren still has a higher power-to-weight ratio than Veyron !  Another aspect the F1 so different from contemporary

supercars is its compact size. It was a good 640 mm shorter than Jaguar

XJ220, 220 mm narrower than Lamborghini Diablo, yet it had the longest

wheelbase to aid high-speed stability. On the one hand, its compactness means it should

be more manageable on narrow country roads than

contemporary supercars. On the other hand, its smaller frontal area benefited drag

and, combined with a good Cd of 0.32 and a powerful engine, it was well

positioned to break

the world speed record.

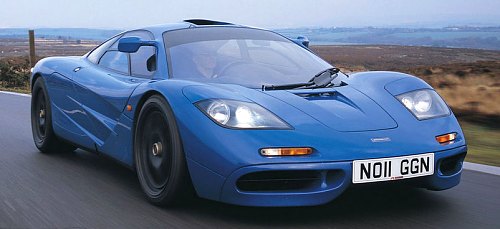

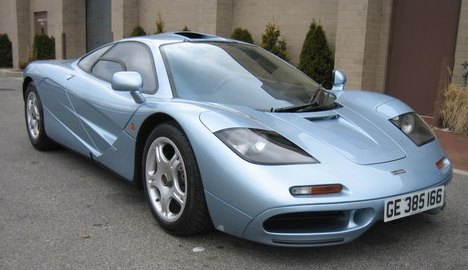

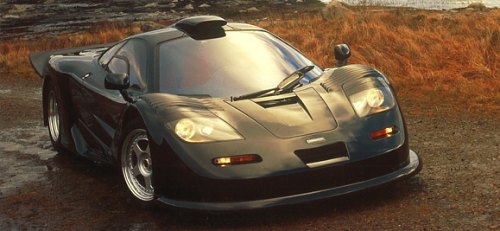

Active aerodynamics also set it apart from contemporary supercars. Inside the tail there are two electric fans. They suck air from the ground towards the tail, generating ground effect like the Brabham fan car. When the car is under braking, its raises the rear spoiler, generating extra downforce at the tail to counter-balance the car. This keeps its weight distribution constant and enhances braking performance. Most brilliant, all these advanced functions did not compromise style. The F1 was styled by British designer Peter Stevens, who has Jaguar XJR-15, Lotus Elan M100 and Esprit X180 under his name. However, the McLaren remains to be his greatest design. Perhaps not as spectacular as some Italian supercars, it is unquestionably beautiful, well proportioned and perfectly executed. It looks like a Group C endurance sports car morphed into a compact road car and finished with many stylish touches. Its sense of very high build quality was achieved by the tight tolerance of its carbon-fiber panels and perfect paint work, thanks to McLaren's wealth of experience in building and painting its Formula One race cars. Sense of occasion is given by its butterfly doors and roof-mounted engine intake, which goes straight through a tunnel towards the engine. This car is a good example that forms can work in harmony with functions.   Then there is a mighty 6.1-liter V12.

BMW was very generous to take up what Honda refused to do. It developed

a bespoke engine for the car only in exchange for publicity. This was

easily the best high-performance engine in the world, one that

overwhelmed

Ferrari boxer-12, Lambo V12 and the turbocharged

engines from Bugatti and Jaguar. Never before had we heard a

large-capacity

naturally aspirated engine could achieve a specific output of 103 hp

per liter, neither had we known a road-going engine capable of

delivering over 600 horsepower in a reliable manner. It had all the

state of the art technologies you could dream of, such as infinitely

variable cam phasing (Bi-Vanos) at

all four camshafts, 11.0:1 compression, Nikasil coating, dry-sump

lubrication and individual electronic throttle for each cylinder.

Aluminum heads and block, magnesium cam covers and oil pan and

carbon-fiber air box kept its weight under check, while its compact

packaging fits perfectly into the F1. Behind the engine is a Weismann

transverse 6-speed manual gearbox and limited-slip differential.

The flywheelless V12 is definitely a masterpiece. Like a racing engine, it is free-revving and extremely responsive to throttle. On the other hand, its smooth and linear power delivery is much to be appreciated versus the laggy turbocharged motors in Bugatti EB110, Jaguar XJ220 and Ferrari F40. It also sounds more delicious to ears. Most important, it produces 627 horsepower at 7400 rpm, good enough to propel the F1 prototype to 231 mph at Nardo test track. That exceeded its nearest rivals by nearly 20 mph*, the biggest leap we had ever seen. However, that did not show its real potential. In April 1998, McLaren took the F1 to Volkswagen's Ehra-Leissen test track. This time with its 7500 rpm rev-limiter disabled (otherwise remained stock), it recorded a two-way average of 240.1 mph. Yes, the F1 road car was actually faster than real F1 cars ! Remark: * Stock Jaguar XJ220 and Bugatti EB110 recorded 212 mph and 209 mph respectively by independent tests.   Equally astonishing is its acceleration. Back in 1994,

Autocar magazine published some stunning results from its road test:

In other words, it simply blew away its oppositions. These figures remained unbeatable until Bugatti Veyron arrived 12 years later. Then again, the McLaren did not have advanced launch control, dual-clutch transmission, modern tires and 4WD system as in the newer Bugatti. Its speed is simply the result of its excellent power-to-weight ratio, low drag and good weight distribution - those principles that racing engineers adore. That is also what made the F1 so appealing to purists.  Nevertheless, to say the F1 a perfect car would be a little

exaggerated. While road testers always praised its performance, few

gave the same credit to its handling. With a power-to-weight ratio of

550 horsepower per ton yet without the aid of traction or stability

control, it would be foolish to assume an easy drive. The fact that two

of the four prototypes crashed during development was a

testament to its untamed character.

Gordon Murray rejected all kinds of electronic driving aids because he preferred pure driver control over complication (which means weight). This might be right in the view of the premature electronic technology then. However, considering the massive power it possesses, the F1 is relatively weak in the chassis department. Most people prefer the handling of Ferrari F50 to that of the McLaren because it is more stable in bends. Comparactively, the F1 understeers and rolls quite a lot in corners. Maneuver through slow corner needs special precaution - if you apply too much power, it will run into oversteer and swap ends. The 315/45ZR17 rear tires are just not grippy enough to take on so much power. Another problem is the lack of power assistance. By today's standard, its unassisted steering is incredibly heavy, although its accuracy and feel are beyond doubt. Worse still is the braking, not only demands a strong foot but also delivers too little. The 4-pot Brembo calipers and cross-drilled ventilated discs measuring 332mm front and 305mm rear might be about the best of its days, but compare with today's monster-size carbon-ceramic items they are nothing. Brake fade appears after just a couple of quick laps. It is probably the weakest link in the F1.  So the F1 is designed for advanced drivers. It's not the kind of modern supercars that a monkey can jump into it and drive straight to the horizon. Its flawed controls and handling take a lot of skill and learning to master. Should you do that, it will be a great satisfaction. Now looking back, the F1 is still the definitive supercar we have ever seen. Bugatti and Koenigsegg might produce faster cars now, but neither come close to the greatness of McLaren. Its vision and innovation are still beyond the reach of its rivals. Its beauty still turns more heads. Its 3-seat accommodation and visibility won't be bettered. Moreover, it is still the only supercar you can drive cross-country with your luggage, storm a session of Autobahn at 200-plus mph, slip into the narrow streets of Paris, polish your skill on Scottish country roads and enjoy the envy sights outside London's pubs. Besides, don't forget its glorious racing history - F1 GTR won world GT championships in 1995 and 96, and was the only road-car-based machine that won Le Mans in modern times. No other supercars could be so versatile. That said, the F1 did not enjoy the commercial success it deserved. If it were born today, it would have been a great success. Unfortunately, in the early 1990s the world was hit by recession, which bursted the supercar bubble and dried up demand for ultra-expensive cars. Priced at a sky-high £600,000, the F1 was inevitably a victim. The original production plan of 300 cars shrank to only 100. By 1998, it was over. The project caused substantial loss to McLaren Cars. Today, a good condition F1 can easily costs multiple times of its original price, and its value is almost certain to go up. It becomes the most sought after modern classic. Derivatives

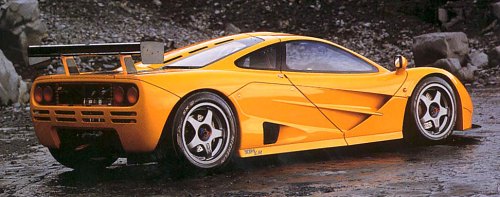

From 1994 to May 1998, McLaren built a total of 100 F1s, 72 of which were road cars and the remaining were GTR race cars. Among the road cars, 64 were the standard F1, 5 were F1 LM and 3 were F1 GT. GTR consists of three generations - GTR ’95, GTR ’96 and GTR ’97, with production numbers of 9, 9 and 10 cars respectively. The LM is the most powerful and most accelerative F1 of all. Basically, it is the street version of the GTR ’95 race car, which won International GT championship and Le Mans in 1995. The removal of air restrictor enabled the V12 engine to output 680 hp instead of the GTR’s 600 hp or the standard car's 627 hp. Besides, it retained many weight saving measures of GTR, such as the deletion of equipment and the use of lighter trimming. Fan-assisted ground effect and automatic rear spoiler were replaced by a simple and effective big rear wing which increased downforce a lot in the expense of top speed. Consequently, the F1 LM could barely reach 225 mph, according to McLaren. However, weighing just 1062 kg, it is 76 kg lighter than the F1 yet has more punch. Therefore acceleration should be even more astonishing. In November, 1999, CAR magazine witnessed McLaren’s test driver Andy Wallace driving the F1 LM to set the world record for 0-100mph-0 in 11.5 sec. The previous record was held by Caterham Seven JPE with a time of 12.41.   The GT was the last road-going F1 produced. Mechanically it differed little from the standard F1, but the bodywork was vastly modified. Its tail was massively extended, accompany with a longer nose, to enhance downforce without adding the slightest drag. Overall width was extended by 120 mm, accompany with widened tracks and skirts, to give a more racing-car profile, thus improved cornering balance. These changes mirrored the ’97 GTR.  From near to far: F1, F1 LM and F1 GT |